Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2

Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) er et kamera, der var installeret i Hubble-rumteleskopet. Det blev installeret under rumfærgens servicebesøg 1 (STS-61) i 1993, hvor teleskopets originale Wide Field and Planetary Camera (WF/PC) blev udskiftet. WFPC2 benyttedes bl.a. til at optage billederne af Hubble Deep Field i 1995, og af Timeglastågen og Æggetågen i 1996.

Under rummissionen STS-125 blev WFPC2 demonteret fra Hubble-rumteleskopet og erstattet med Wide Field Camera 3 som en del af missionens første rumvandring den 14. maj 2009. WFC3 er udstyret med to CCD'er til UV/synligt lys-området, hver på 2048x4096 pixels, og en selvstændig CCD på 1024 x 1024, der er i stand til at modtage infrarød stråling op til 1700 nm. Efter at være tilbage på Jorden blev WFP2 kortvarigt udstillet på National Air and Space Museum og Jet Propulsion Laboratory før det blev permanent placeret på Smithsonians National Air and Space Museum.[1][2]

WFPC2 indeholder 4 ens CCD-sensorer, hver på 800x800 pixels. De registrerer elektromagnetisk stråling i området fra 120 nm til 1100 nm. Dette område inkluderer det synlige spektrum fra 380 nm til 780 nm, hele det nære ultraviolette (og en lille del af det yderste ultraviolette bånd) og størstedelen af det nære infrarøde bånd. Fordelingen af følsomheden i disse CCD'er er tæt på at være normalfordelt med en top omkring 700 nm og følgelig med meget ringe følsomhed ved de yderste grænser for CCD'ernes operationsområde. Tre af de fire CCD'er, der sidder i form som et L, udgør Hubbles Wide Field Camera (WFC). Den fjerde CCD, som støder op til dem, er det såkaldte Planetary Camera (PC), som er udstyret med en optik med snævrere fokus. Det giver et mere detaljeret kig på en mindre del af det synlige område. Billederne fra WFC og PC bliver typisk samlet til et enkelt billede, som udviser en "trappetrins-form", der er karakteristisk for WFPC2. Når der frigives JPEG-filer til ikke-videnskabeligt brug, vises billedets PC-del i samme opløsning som WFC-delene, men astronomer modtager en billedfil til videnskabelig brug, hvor PC-billedet findes i sin oprindelige, højere opløsning.

For at gøre det muligt for videnskabsmændene at betragte enkelte dele af det elektromagnetiske spektrum er WFPC2 forsynet med et drejeligt hjul, som kan sætte forskellige optiske filtre ind i lysstrålen (mellem WFPC2's åbning og CCD-detektorerne). WFPC2 har 48 filterelementer, som omfatter:

- Et polarisationsfilter.

- Et gradueret filter med en hel række filtre med meget lille båndbredde. Ved at positionere det betragtede objekt i den præcise del af området kan operatøren bruge et omhyggeligt udvalgt snævert filter (omend kun over en meget lille del af området.

- En antal forskellige optiske filtre, som giver operatøren en række valgmuligheder mellem forskellige karakteristika for optagelsen.

Som det var forudset fra starten, er CCD'erne i WFPC2 i løbet af deres brugstid blevet forringet, hvilket viser sig i form af oplyste enkeltpixels. Teleskopets operatører gennemfører månedlige kalibreringsprøver for at finde disse: Der tages et antal billeder, mens WFPC's åbning er dækket til, og de pixels, som afviger væsentligt fra næsten sort bliver markeret. For at undgå at fejlmarkere pixels, som kun lyser, fordi de er midlertidig ramt af kosmisk stråling, sammenlignes resultatet af forskellige kalibreringer. Her findes de pixels, som vedblivende lyser op, og astronomerne, der analyserer grundmaterialet til WFPC2's billeder, modtager en liste over disse pixels. Som regel benytter kan de benytte listen til at modificere deres billedbehandlingssoftware, så de dårlige pixels ignoreres.

WFPC2 blev bygget af NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, som også byggede dets forgænger WFPC-kameraet ("WFPC1"), der oprindeligt blev opsendt med Hubble i 1990. WFPC2 har sin egen interne korrektionsoptik, som kan justere den sfæriske aberration i Hubble-teleskopets primære spejl.

WFPC2-billeder

Referencer

- ^ ""The Camera that Saved Hubble" Coming to the Smithsonian". 27. maj 2009. Arkiveret fra originalen 13. oktober 2010. Hentet 14. juli 2009.

- ^ "The Camera That Saved Hubble Leaves the Nest". JPL / NASA. Arkiveret fra originalen 7. februar 2012. Hentet 14. oktober 2010.

Eksterne henvisninger

Denne artikel har en liste med kilder, en litteraturliste eller eksterne henvisninger, men informationerne i artiklen er ikke underbygget, fordi kildehenvisninger ikke er indsat i teksten. (2023) |

- WFPC2 hjemmeside og brugermanual

- NASA artikel, som forklarer, hvorledes farver tildeles fra billeder optaget med flere forskellige filtre

- Om Wide Field Camera 3 – NASA Arkiveret 29. august 2005 hos Wayback Machine

- WFPC2 på ESA/Hubbles side Arkiveret 20. marts 2007 hos Wayback Machine

- Billeder taget af WFPC2 og vist på ESA/Hubbles side Arkiveret 30. september 2007 hos Wayback Machine

Medier brugt på denne side

Resembling a rippling pool illuminated by underwater lights, the Egg Nebula (CRL 2688) offers astronomers a special look at the normally invisible dust shells swaddling an aging star. These dust layers, extending over one-tenth of a light-year from the star, have an onionskin structure that forms concentric rings around the star. A thicker dust belt, running almost vertically through the image, blocks off light from the central star. Twin beams of light radiate from the hidden star and illuminate the pitch-black dust, like a shining flashlight in a smoky room.

The artificial "Easter-Egg" colors in this image are used to dissect how the light reflects off the smoke-sized dust particles and then heads toward Earth.

Dust in our atmosphere reflects sunlight such that only light waves vibrating in a certain orientation get reflected toward us. This is also true for reflections off water or roadways. Polarizing sunglasses take advantage of this effect to block out all reflections, except those that align to the polarizing filter material. It's a bit like sliding a sheet of paper under a door. The paper must be parallel to the floor to pass under the door.

Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys has polarizing filters that accept light that vibrates at select angles. In this composite image, the light from one of the polarizing filters has been colored red and only admits light from about one-third of the nebula. Another polarizing filter accepts light reflected from a different swath of the nebula. This light is colored blue. Light from the final third of the nebula is from a third polarizing filter and is colored green. Some of the inner regions of the nebula appear whitish because the dust is thicker and the light is scattered many times in random directions before reaching us. (Likewise, polarizing sunglasses are less effective if the sky is very dusty).

By studying polarized light from the Egg Nebula, scientists can tell a lot about the physical properties of the material responsible for the scattering, as well as the precise location of the central (hidden) star. The fine dust is largely carbon, manufactured by nuclear fusion in the heart of the star and then ejected into space as the star sheds material. Such dust grains are essential ingredients for building dusty disks around future generations of young stars, and possibly in the formation of planets around those stars.

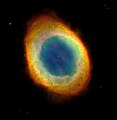

The Egg Nebula is located 3,000 light-years away in the constellation Cygnus. This image was taken with Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys in September and October 2002.السديم الحلقي، سديم كوكبي مشابه لما ستصبح عليه الشمس.

Strangely glowing dark clouds float serenely in this remarkable and beautiful image taken with the Hubble Space Telescope. These dense, opaque dust clouds — known as globules — are silhouetted against nearby bright stars in the busy star-forming region, IC 2944.

Astronomer A.D. Thackeray first spied the globules in IC 2944 in 1950. Globules like these have been known since Dutch-American astronomer Bart Bok first drew attention to such objects in 1947.

But astronomers still know very little about their origin and nature, except that they are generally associated with areas of star formation, called HII regions due to the presence of hydrogen gas. IC 2944 is filled with gas and dust that is illuminated and heated by a loose cluster of massive stars. These stars are much hotter and much more massive than our Sun.Star forming pillars in the Eagle Nebula, as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope's WFPC2. The picture is composed of 32 different images from four separate cameras in this instrument. The photograph was made with light emitted by different elements in the cloud and appears as a different colour in the composite image: green for hydrogen, red for singly-ionized sulphur and blue for double-ionized oxygen atoms. The missing part at the top right is because one of the four cameras has a magnified view of its portion, which allows astronomers to see finer detail. The images from this camera were scaled down in size to match those from the other three cameras. Further information at: Credit: NASA, Jeff Hester, and Paul Scowen (Arizona State University)

The photograph, taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, captures a small region within M17, a hotbed of star formation. M17, also known as the Omega or Swan Nebula, is located about 5500 light-years away in the constellation Sagittarius.

The wave-like patterns of gas have been sculpted and illuminated by a torrent of ultraviolet radiation from young, massive stars, which lie outside the picture to the upper left. The glow of these patterns accentuates the three-dimensional structure of the gases. The ultraviolet radiation is carving and heating the surfaces of cold hydrogen gas clouds. The warmed surfaces glow orange and red in this photograph. The intense heat and pressure cause some material to stream away from those surfaces, creating the glowing veil of even hotter greenish gas that masks background structures. The pressure on the tips of the waves may trigger new star formation within them.

The image, roughly 3 light-years across, was taken May 29-30, 1999, with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2. The colors in the image represent various gases. Red represents sulfur; green, hydrogen; and blue, oxygen.This is a Hubble Space Telescope image (right) of a vast nebula called NGC 604, which lies in the neighboring spiral galaxy M33, located 2.7 million light-years away in the constellation Triangulum.

This is a site where new stars are being born in a spiral arm of the galaxy. Though such nebulae are common in galaxies, this one is particularly large, nearly 1,500 light-years across. The nebula is so vast it is easily seen in ground-based telescopic images (left).

At the heart of NGC 604 are over 200 hot stars, much more massive than our Sun (15 to 60 solar masses). They heat the gaseous walls of the nebula making the gas fluoresce. Their light also highlights the nebula's three-dimensional shape, like a lantern in a cavern. By studying the physical structure of a giant nebula, astronomers may determine how clusters of massive stars affect the evolution of the interstellar medium of the galaxy.

The nebula also yields clues to its star formation history and will improve understanding of the starburst process when a galaxy undergoes a "firestorm" of star formation. The image was taken on January 17, 1995 with Hubble's Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2. Separate exposures were taken in different colors of light to study the physical properties of the hot gas (17,000 degrees Fahrenheit, 10,000 degrees KelvinForfatter/Opretter: Maggie Masetti, Licens: CC BY 2.0

Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2). The holes you see are from micrometeorite impacts that were later sampled for study.