Kvantemekanisk atommodel

Den kvantemekaniske atommodel eller kvantefysiske atommodel er grundlæggende baseret på Bohrs atommodel,[1] men elektronerne og atomkernen beskrives som tredimensionelle stående bølger – tredimensionale sandsynlighedsfordelinger i stedet for punkter. Elektronernes sandsynlighedsfordeling bliver også benævnt "elektronskyer" eller orbitaler.[1][2][3][4] Det var Erwin Schrödinger der fremsatte en formel for sandsynligheden for at finde elektronen forskellige steder rundt om atomkernen. Denne ligning hedder Schrödingers ligning og forklarer sandsynligheden for position af elektronen for forskellige tider.

Denne teori blev eftervist af dobbeltspalte-eksperiment fordi dette viste partikler, vi troede kun var punktformige, kunne lave interferens med sig selv. Hvis man sender fx en elektromagnetisk stråling igennem de to spalter i dobbeltspalte-eksperimentet, ville dette give et interferensmønster (skiftevis detektion og ikke detektion) fordi bølgerne vil neutralisere hinanden hvor bølgetop og bølgedal mødes, og for forstærke hinanden når to bølgetoppe eller bølgedale mødes. Hvorimod hvis det var partikler, ville man detekte to streger svarende til spalterne direkte bag spalterne fra kilen.

Kilder/referencer

- ^ a b arxiv.org: The many faces of the Bohr atom. Helge Kragh. Centre for Science Studies, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Aarhus University. Citat: "...Bohr’s theory of 1913 was much more than just a theory of the hydrogen atom. In the second part of the trilogy he ambitiously proposed models also of the heavier atoms, picturing them as planar systems of electrons revolving around the nucleus. The lithium atom, for example, would consist of two concentric rings, an inner one with two oppositely located electrons and an outer one with a single electron...However, latest by 1920 it was realized that the planar ring atom was inadequate and had to be replaced by a more complex model that made both chemical and physical sense.13...In the Bohr-Kramers-Slater (BKS) theory from 1924, describing the atom as an orchestra of virtual oscillators, the electrons orbiting in stationary states had finally disappeared...."

- ^ Web archive backup: Milo Wolff's Quantum Science Corner's: The Quantum Universe Citat: "...Actually, in the H atom both the electron wave-structure and the proton have the same center. The electron's structure can be imagined like an onion – spherical layers of waves around a center. The amplitude of the waves decreases like the blue standing wave in the bottom diagram. There are no point masses – no orbits, just waves...".

- ^ Web archive backup: Atomic Orbitals

- ^ The Orbitron a gallery of atomic orbitals and molecular orbitals on the WWW.

Se også

Eksterne henvisninger

- 8 August 2002, physicsworld.com: Electrons probe single atoms

- 24 October 2002, physicsworld.com: First light for attophysics

- 20 June 2001, Quantum spin probe able to measure spin states at individual atoms; could have application in quantum computing

- 16 Feb 2000 First-ever images of atom-scale electron clouds in high-temperature superconductors could help in design of new and better materials.

- Number 554 #1, August 30, 2001, AIP: Evidence for the Onset of Quark Effects Arkiveret 3. februar 2004 hos Wayback Machine Citat: "...When a particle strikes a nucleus at high energies, however, it penetrates the nucleus so deeply that this "effective theory" breaks down, and one must describe the nuclear action in terms of only quarks and gluons..."

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Medier brugt på denne side

Forfatter/Opretter: Ukendt, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

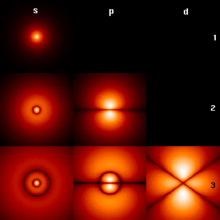

First few hydrogen atom orbitals; cross section showing color-coded probability density for different n=1,2,3 and l="s","p","d"; note: m=0

The picture shows the first few hydrogen atom orbitals (energy eigenfunctions). These are cross-sections of the probability density that are color-coded (black=zero density, white=highest density). The angular momentum quantum number l is denoted in each column, using the usual spectroscopic letter code ("s" means l=0; "p": l=1; "d": l=2). The main quantum number n (=1,2,3,...) is marked to the right of each row. For all pictures the magnetic quantum number m has been set to 0, and the cross-sectional plane is the x-z plane (z is the vertical axis). The probability density in three-dimensional space is obtained by rotating the one shown here around the z-axis.

Note the striking similarity of this picture to the diagrams of the normal modes of displacement of a soap film membrane oscillating on a disk bound by a wire frame. See, e.g., Vibrations and Waves, A.P. French, M.I.T. Introductory Physics Series, 1971, ISBN 0393099369, page 186, Fig. 6-13. See also Normal vibration modes of a circular membrane.