Kritik af Jesus

Kritik af Jesus har eksisteret siden det første århundrede. Jesus blev kritiseret af farisæere og skrivere for at bryde moseloven. Han blev afvist i jødedommen som en falsk Messias og falsk profest af de fleste jødiske trossamfund. Jødedommen betragter også tilbedelse af enhver person som en form for afgudsdyrkelse,[4][5] og afviser Jesu påstand om at være guddommelig. Nogle psykiatere, religionshistorikere og forfattere beskriver at Jesus' familie, følgere og samtidige opfattede ham som det at have vrangforestillinger, være besat af dæmoner eller være sindssyg.[6][7][8][9][10]

Tidlige kritikere af Jesus og kristendommen inkluderer Celsus i det andet århundrede og Porfyr i det tredje årh.[11][12] I 1800-tallet var Friedrich Nietzsche meget kritisk over for Jesus og sin samtids udgave af kristendommen - romantikkens udtynding af livet, hvis lære han betragtede som værende "anti-natur" i deres behandling af emner som seksualitet. Mere moderne kritikere af Jesus inkluderer Ayn Rand, Hector Avalos, Sita Ram Goel, Christopher Hitchens, Bertrand Russell, og Dayananda Saraswati.

Se også

- Afvisning af Jesus (en)

- Den historiske Jesus

- Jesu mentale sundhed (en)

- Kritik af kristendommen (en)

Referencer

- ^ The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009 ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 pp. 104–108

- ^ Evans, Craig A. (2001). Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies ISBN 0-391-04118-5 p. 316

- ^ Wansbrough, Henry (2004). Jesus and the Oral Gospel Tradition ISBN 0-567-04090-9 p. 185

- ^ Kaplan, Aryeh (1985). The real Messiah? a Jewish response to missionaries (New udgave). New York: National Conference of Synagogue Youth. ISBN 978-1879016118. The real Messiah (pdf)

- ^ Singer, Tovia (2010). Let's Get Biblical. RNBN Publishers; 2nd edition (2010). ISBN 978-0615348391.

- ^ Havis, Don (april-juni 2001). "An Inquiry into the Mental Health of Jesus: Was He Crazy?". Secular Nation. Minneapolis: Atheist Alliance Inc. ISSN 1530-308X. Hentet 29. marts 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato-format (link) - ^ Murray, Evan D.; Cunningham, Miles G.; Price, Bruce H. (oktober 2012). "The Role of Psychotic Disorders in Religious History Considered". Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. American Psychiatric Association. 24 (4): 410-426. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11090214. ISSN 1545-7222. OCLC 823065628. PMID 23224447. S2CID 207654711.

- ^ Meggitt, Justin J. (1. juni 2007). "The Madness of King Jesus: Why was Jesus Put to Death, but his Followers not?". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. London: SAGE Publications. 29 (4): 379-413. doi:10.1177/0142064X07078990. ISSN 0142-064X. S2CID 171007891.

- ^ Hirsch, William (1912). Religion and Civilization: The Conclusions of a Psychiatrist. New York: The Truth Seeker Company. s. 135. LCCN 12002696. OCLC 39864035. OL 20516240M.

That the other members of his own family considered him insane, is said quite plainly, for the openly declare, "He is beside himself."

- ^ Kasmar, Gene (1995). All the obscenities in the Bible. Brooklyn Center, MN: Kas-mark Pub. Co. s. 157. ISBN 978-0-9645-9950-5.

He was thought to be insane by his own family and neighbors in 'when his friends heard of it, they went out to lay hold on him: for they said, He is beside himself ... (Mark 3:21-22 – The Greek existemi translated beside himself, actually means insane and witless), The Greek word ho para translated friends, also means family.

- ^ Chadwick, Henry, red. (1980). Contra Celsum. Cambridge University Press. s. xxviii. ISBN 978-0-521-29576-5.

- ^ Stevenson, J. (1987). Frend, W. H. C. (red.). A New Eusebius: Documents illustrating the history of the Church to AD 337. SPCK. s. 257. ISBN 978-0-281-04268-5.

| Spire Denne religionsartikel er en spire som bør udbygges. Du er velkommen til at hjælpe Wikipedia ved at udvide den. |

Medier brugt på denne side

Forfatter/Opretter: Michaelovic, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

Logo for the Dutch Wikipedia religion and filosofycafé

Before enrolling in the École des Beaux-Arts, Scheffer studied with the neoclassically trained artist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whose mastery of the art of the past and high technical finish he emulated. He exhibited his first works at the age of 17 in the 1812 Salon in the so-called "juste-milieu" (in English, literally, middle path) tradition. Scheffer was attracted to romantic themes gleaned from contemporary authors such as Sir Walter Scott and Goethe. His meteoric rise in the art world drew instant critical acclaim and the acquaintance of such artists as Théodore Géricault, Eugène Delacroix, and Paul Delaroche.

This work was not seen until after Scheffer's death. He stopped exhibiting at the Salon altogether in 1846 and became increasingly preoccupied with religious imagery with a seriousness that reflects a pointed departure from his earlier, more anecdotal work. In this iconic image, he focuses on the solitary figure of Christ, who is weeping for the coming destruction of Jerusalem, as described by the Evangelist Luke in the New Testament (19:41): "As he came near and saw the city, he wept over it."

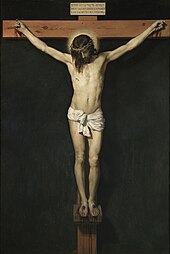

La obra representa a Jesucristo crucificado, y es una de las obras religiosas más conocidas del pintor sevillano Diego Velázquez.