Eva Bonnier

| Eva Bonnier | |

|---|---|

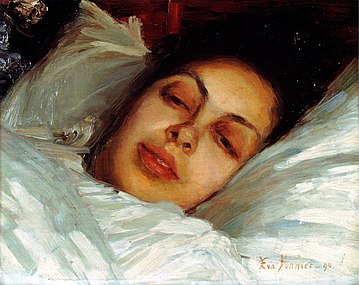

Selvportræt, 1886. Bonniers portrætsamling | |

| Personlig information | |

| Født | 17. november 1857 Stockholm, Sverige |

| Død | 13. januar 1909 (51 år) København, Danmark |

| Gravsted | Mosaiska kyrkogården Norra begravningsplatsen |

| Far | Albert Bonnier |

| Mor | Betty Bonnier |

| Søskende | Karl Otto Bonnier |

| Uddannelse og virke | |

| Uddannelsessted | Fruntimmersavdelningen vid Kungliga Akademien för de fria konsterna, Kungliga Konsthögskolan, Académie Colarossi, August Malmströms Kunstskole |

| Medlem af | Grezkolonien |

| Beskæftigelse | Kunstmaler |

| Fagområde | Kvindernes stemmeret i Sverige |

| Deltog i | Svenska konstnärinnornas utställning |

| Arbejdssted | Stockholm |

| Kendte værker | Atelierinteriør i Paris, Fru Hanna Marcus, Refleks i blåt |

| Genre | Portræt |

| Bevægelse | Impressionisme |

| Information med symbolet | |

Eva Fredrika Bonnier (født 17. november 1857 i Stockholm ; død 15. januar 1909 i København) var en svensk portrætmaler og en af de førende svenske kvindelige kunstnere i sidste del af det 19. århundrede.[1][2] Hun var datter af forlægger Albert Bonnier og hans første kone Betty Rubenson.

Eva Bonnier var medlem af det svenske Konstnärsförbundet og er repræsenteret på Nationalmuseum[3], Blekinge Museum og Bonniers portrætsamling, og hendes arbejde har også været udstillet på Parisersalonen[1] 1889, Verdensudstillingen i Chicago 1893, Liljevalchs konsthall, Millesgården, Thielska galleriet och Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde.[4]

Liv og karriere

Eva Bonnier begyndte i 1875 på August Malmströms Kunstskola og fortsatte efterfølgende på Kvindeafdelingen af Kunstakademiet i Stockholm. I 1883 flyttede hun, ligesom mange andre kvindelige nordiske kunstnere i tiden til Paris, hvor hun boede på Mont Martre. Grundet hendes familiære forhold med opvæksten i en meget velhavende jødisk og højborgerligt familie i Stockhom, var hun hele livet økonomisk uafhængig og levede et meget frigjort kvindeliv i forhold til sin tid.

Hun var forlovet med billedhuggeren Per Hasselberg, som hun skulle have været gift med i 1892, men forlovelsen blev afbrudt. Da Per Hasselberg efterfølgende døde i 1894, adopterede Eva Bonnier hans uægte barn, Julia.

I 1894 flyttede hun tilbage til Stockholm med Julia, hvor hun startede med at lave bestillingsopgaver på portrætmalerier. Senere holdt hun op med at male grundet manglende tro på egne evner som kunstner. I stedet fyldte hendes rolle som mæcen for svenske kunstnere stadigt mere, idet hun opkøbte kunst til offentlige bygninger.

Eva Bonnier led af depressioner og tog sit eget liv i 1909 (51 år gammel). [5]

Kunstnerisk formsprog

Eva Bonnier var realist og skildrede både i sine malerier og skulpturer sine modeller med stor præcision og psykologisk indsigt.[6]

Hun havde særligt i starten af sin kunstneriske karriere en stor produktion af portrætter og menneskeskildringer. Interiører og komplicerede lyseffekter fylder også meget i hendes malerier.[5]

|

|

Referencer

- ^ a b Eva F Bonnier i Svenskt biografiskt lexikon af Tor Hedberg.

- ^ Thorsell, Elisabeth (sv), red. (2004). Gerhard Bonniers ättlingar (svensk). Stockholm. s. 24.Libris 9819839

- ^ Eva Bonnier hos Nationalmuseum

- ^ Listning af udstillinger ses her : "Utställningar"

- ^ a b Gynning, Margareta (1999). Det Ambivalenta Perspektivet (svensk), Albert Bonniers Förlag, s. 17

- ^ Bo Bierlich, Emilie (2024) Værkfortællinger i Against All Odds, Statens Museum for Kunst, s. 91.

- ^ Fru Hanna Marcus hos Digitaltmuseum.se

- ^ Doneret 2013 af Eva Bonniers brors barnebarn professor Yngve Larsson

- ^ Om billedet 'Hushållerskan' fra Nationalmuseum.se via Archive.org. Hun hed Maria Banck ('Mussa')

Eksterne henvisninger

- Eva Bonnier i Nationalmuseums samlinger

- Bonnier, Eva i Libris (svensk) (Svensk bibliotekskatalog)

- Eva Fredrika Bonnier i Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon, SKBL

- Eva Bonnier i kunstnerleksikonet Amanda

Medier brugt på denne side

Image scanned from the book "Svenskt Porträttgalleri XX - Arkitekter, Bildhuggare, Målare m.fl. " ("Swedish Portrait Gallery XX - Architects, Sculptors, Painters, ") published 1901

Hanna Marcus was a relative of some friends of Eva Bonnier’s. This portrait was painted on Dalarö, south of Stockholm, where many of the artist’s acquaintances spent the summer. It was probably not a commissioned work, but seems to have been done on Bonnier’s own initiative – as its modest size and intimate character suggest. This is one of the paintings Richard Bergh, artist and director of the Nationalmuseum, acquired for the Museum in 1915 to strengthen its collection of important works from the late 19th century.

Eva Bonnier’s depictions of terminal illness, bring us a pared-down everyday perspective, with the artist challenging the stereotypical female bourgeois ideal of the time. Women are presented as “subjects” with strong integrity and not as fragile objects. In Reflection in Blue, from 1887, the figures are painted from a realistic perspective, placing us in the same room as the ailing person.

Around the turn of the 20th century, convalescing women are a popular theme in art. Those images should be seen in the context of the prevailing view of and construction of femininity, and thus of the standardisation of the female body. During the 19th century, two key images of women evolved: the weak, sensitive and psychosomatic upper class woman and the strong, dangerous and infectious lower class woman. The “Convalescent” became a symbol of female fragility and thus evidence of women’s inability to take part in public life. Those images can be seen as a reaction to the emancipation of women at the time and as an attempt to return them to the home and the private sphere.

But in the Nordic region one could find many hundreds of female artists and authors during this period. The female artists in Sweden were privileged compared with their European sisters, since they had access to an academic education. The women’s department of the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm opened in 1864, and the professional women had a major influence on the cultural life of the period. They changed both the view of the role of the artist and that of middle-class family life, and in so doing they shook the norm of the male artist to the core. But at the turn of the century there was a backlash and women’s emancipation was thwarted, together with a widespread fear of the “New Woman”.Eva Bonnier was one of many Swedish women artists who studied and worked in Paris in the 1880s. This painting shows a corner of the studio she rented in Montparnasse in 1885–1887. A boy’s head in clay is on the modeling stand. Bonnier was active mainly as a portrait painter. She herself has said that she made the sculpture when she needed a change from painting. The model was described in a letter home as “a little urchin, and therefore not inclined to sit still, but from an Italian family of models”.

Albert Bonnier och_Betty_med_barnen

![Fru Hanna Marcus, 1886. Nationalmuseum[7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/Old_Grandmother_%28Eva_Bonnier%29_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18858.tif/lossy-page1-226px-Old_Grandmother_%28Eva_Bonnier%29_-_Nationalmuseum_-_18858.tif.jpg)

![Magdalena, 1887. Prins Eugens Waldemarsudde (sv)[8]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Eva_Bonnier%2C_Magdalena%2C._1887%2C_W_2569%2C_Waldemarsudde%2C_Stockholm.jpg/340px-Eva_Bonnier%2C_Magdalena%2C._1887%2C_W_2569%2C_Waldemarsudde%2C_Stockholm.jpg)

![Husholdersken, 1890, Nationalmuseum – Maria Banck, 'Mussa' (1830-1906)[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/48/The_Housekeeper%2C_Brita_Maria_%28Mussa%29_Banck_%28Eva_Bonnier%29_-_Nationalmuseum_-_40071.tif/lossy-page1-218px-The_Housekeeper%2C_Brita_Maria_%28Mussa%29_Banck_%28Eva_Bonnier%29_-_Nationalmuseum_-_40071.tif.jpg)