Den gamle te-handelsrute

Den gamle te-handelsrute eller chamadao (forenklet kinesisk: 茶 马 道; traditionel kinesisk: 茶 馬 道), der nu generelt kaldes "den gamle te-hesterute" eller chamagudao (forenklet kinesisk: 茶 马 古道; traditionel kinesisk: 茶 馬 古道) var et netværk af karavanestier, der snoede sig gennem bjergene i Sichuan, Yunnan og Guizhou i det sydvestlige Kina.[1] Den kaldes også undertiden for "den sydlige silkevej". Ruten forlængedes til Bengalen i Sydasien.

Historie

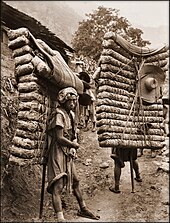

Omkring år 1.000 e.Kr. var den gamle te-rute en handelsforbindelse fra Yunnan, der var en af de første teproducerende regioner: til Bengalen via Burma, til Tibet og til det centrale Kina via Sichuan-provinsen.[2][3][4][5][6] Ud over te fragtede muldyrkaravanerne salt. Både mennesker og heste bragte store ladninger, og tebærerne bar nogle gange over 60-90 kg, hvilket ofte var mere end deres egen kropsvægt i te.[7][8][9] Transportørerne brugte metalstivere ved pakningen af tepakkerne, både for at holde balancen, mens de gik, og for at hjælpe med at understøtte lasten, mens de hvilede, så de ikke behøvede at lægge ballerne direkte på jorden.

Det antages, at det var gennem dette handelsnet, at te (typisk te-pakker) først spredte sig over Kina og Asien fra sin oprindelse i Pu'er-området, nær Simao-præfekturet i Yunnan.[10][11]

Ruten fik navnet te-hesteruten på grund af den fælles handel med tibetanske ponyer for kinesisk te, en praksis, der dateres mindst tilbage til Song-dynastiet, da de robuste heste var vigtige for Kina at bekæmpe krigende nomader i nord.[12]

Fremtid

I det 21. århundrede er arven efter Den gamle te-handelsrute blevet brugt til at fremme en jernbane, der forbinder Chengdu med Lhasa. Denne planlagte jernbane, en del af Folkerepublikken Kinas 13. 5-årsplan, kaldes Sichuan-Tibet Railway (川藏 铁路); Den vil forbinde byer på tværs af ruten, herunder Kangding. Myndigheder hævder, at den vil bringe stor fremgang for de berørte folks velfærd. [13]

Noter

- ^ Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David: Traders of the Golden Triangle (A study of the traditional Yunnanese mule caravan trade). Chiang Mai. Cognoscenti Books, 2011.

- ^ "Horse Corridor in Heaven". Shambhalatimes.org. 2010-01-18. Arkiveret fra originalen 8. juli 2014. Hentet 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Tea-Horse Route". Chinatrekking.com. Arkiveret fra originalen 29. oktober 2013. Hentet 2011-11-18.

- ^ "The road line of the ancient tea-and-horse trade road". Yellowsheepriver.com. Arkiveret fra originalen 29. oktober 2013. Hentet 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Richness, Diversity and Natural Beauty on the Tea Horse Road". English.cri.cn. Arkiveret fra originalen 25. november 2018. Hentet 2011-11-18.

- ^ "Strange Brew:The Story of Puer Tea 普洱茶". Arkiveret fra originalen 13. januar 2015. Hentet 2011-11-28.

- ^ "Between Winds and Clouds: Chapter 2". Gutenberg-e.org. 2007-12-04. Arkiveret fra originalen 18. august 2018. Hentet 2014-08-22.

- ^ "Holiday". Weeklyholiday.net. Arkiveret fra originalen 15. juni 2013. Hentet 2014-08-22.

- ^ "History and Legend of Sino-Bangla Contacts". Bd.china-embassy.org. Arkiveret fra originalen 4. marts 2016. Hentet 2015-05-19.

- ^ Jeff Fuchs. The Ancient Tea Horse Road: Travels with the Last of the Himalayan Muleteers, Viking Canada, 2008. ISBN 978-0-670-06611-7

- ^ Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, 'Pu'er Tea Traditions' in: China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2011.

- ^ Jenkins, Mark (maj 2010). "The Tea Horse Road". National Geographic. Arkiveret fra originalen 16. november 2017. Hentet 26. november 2017.

- ^ "Arkiveret kopi". Arkiveret fra originalen 1. december 2017. Hentet 26. november 2017.

|

Medier brugt på denne side

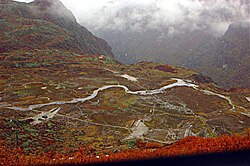

Forfatter/Opretter: Jaryiahr Khan, Licens: CC BY-SA 3.0

Melong valley near Chamdo town, downstream of it (conluded from original desciption "South of Chamdo (Qamdo) town, Chamdo County, Tibet")

Forfatter/Opretter: ralph repo, Licens: CC BY 2.0

Entitled: Two Men Laden With Tea, Sichuan Sheng China, 30 JUL [1908] EH Wilson [RESTORED] Very little retouching except for a few scratches and spots. Minor contrast and sepia tone added. The original resides in Harvard University Library's permanent collection, and can be found using their Visual Information Access (VIA) Search System by using the title.

Ernest Henry "Chinese" Wilson was an explorer botanist who traveled extensively to the far east between 1899 and 1918, collecting seed specimens and recording with both journals and camera. About sixty Asian plant species bear his name. One of his most famous photographs (above) has repeatedly been mistakenly attributed to another legendary botanist (Joseph Rock) who was also working in Asia.

From Wilson's personal notations (with misspellings as is):

"Men laden with 'Brick Tea' for Thibet. One man's load weighs 317 lbs. Avoird. The other's 298 lbs. Avoird.!! Men carry this tea as far as Tachien lu accomplishing about 6 miles per day over vile roads, 5000 ft."

I suspect that Wilson made a mistake; either miscalculating a conversion from Chinese Imperial to European weight measure, or that he believed an inflated figure offered him by a less than honest native. However, others purportedly shared the same beliefs that some porters did in fact, carry upwards of 300 pound loads. In a rare 2003 interview with several retired former porters, still alive and in their 80's. They stated that while the average was really more between 60-110 Kg; they acknowledged that some (only the very strongest) could shoulder a superhuman 150 Kg load; someone like Giant Chang Woo Gow, or one of his kin, perhaps? An excerpt about that interview:

"The Burden of Human Portage

As recently as the first decades of the 20th century, much of the tea transported by the ancient Tea-Horse Road was carried not by mule caravan, but by human porters, giving real substance to the once widely-employed designation ‘coolie’, a term thought to have been derived from the Chinese kuli or ‘bitter labour’. This was particularly true of smaller tracks and trails leading from remote tea-picking areas to the arterial Tea-Horse routes, both in Yunnan and in Sichuan. Perhaps because this human portage played a less economically significant role than the large – sometimes huge – yak, pony and mule caravans, and perhaps because there is little or no romance attached to the piteous sight of over-burdened, inadequately-clad and under-nourished porters hauling themselves and their massive loads across muddy valleys and freezing mountain passes, less information is available to us concerning tea porters than about tea caravans.

Fortunately some black-and-white images of these incredibly wiry, tough, hard-bitten men have come down to us from Sichuan, as well as at least one 150-year-old French-made lithograph from Yunnan, in addition to some rare oral accounts describing the immense difficulties these hardy wretches had to face. In the latter category, as recently as 2003 China Daily carried an interview with four former tea porters in Ganxipo Village, near Tianquan County to the southwest of Ya’an. Now in their 80s, these veterans recall hard times before the completion of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway in 1954 when they would carry almost impossibly heavy loads of Sichuan Pu’er tea over a narrow mountain trail across the freezing heights of Erlang Shan (‘Two Wolves Mountain’) to Luding and onwards, across the Dadu River, to the tea distribution centre at Kangding.

According to 81-year-old former tea porter Li Zhongquan, tea was carried by human portage all the way from Tianquan County to Kangding, a distance of 180km (112 miles) each way on narrow mountain tracks, much of the way at dangerously high altitudes in freezing temperatures. According to Li, an able-bodied porter would carry 10 to 12 packs of tea, each weighing between 6 and 9 kg. To this had to be added 7 to 8 kg of grain for sustenance en route, as well as ‘five or six pairs of homemade straw sandals to change on the way’. The strongest porters could carry 15 packs of tea, making a total load of around 150 kg (330 imperial pounds). ‘The grain lasted no longer than half the journey’, Li remembered, ‘and you had to replenish your food supply at your own expense’. As for the multiple pairs of straw sandals: ‘these would be worn out quickly, as the mountain path was extremely rough’.

To make the portage of such heavy loads possible, and to help guard against the ever-present danger of overbalancing and falling into one of the many deep ravines skirted by the narrow mountain trail, tea porters carried iron-tipped T-shaped walking sticks both to assist in struggling over the steep, rocky path, and to rest the load on, without taking it off their backs, when they paused for breath. A surviving section of the old stone path near Ganxipo Village bears testament to the almost unimaginable difficulties faced by the tea porters in the past; small holes dot the stone slabs of the path at regular intervals of a pace or so, indicating where, over centuries and perhaps even millennia, the porters struck the rock with their iron-tipped sticks as they made their laborious way to and from Kangding.

It is possible to identify the T-shaped walking-and-support sticks used by the tea porters in black and white photographs from a century or more ago, including one taken by the American explorer and botanist E.H. Wilson, who helpfully appends the information: ‘Western Szechuan; men laden with “brick tea” for Thibet. One man's load weighs 317 lbs [144 kilos], the other's 298 lbs [135 kilos]. Men carry this tea as far as Tachien-lu [Kangding] accomplishing about six miles per day over vile roads. Altitude 5,000 ft [1,500m] July 30, 1908’.

For the tea porters of Ganxipo Village, the hardest part of their journey was the climb over Erlang Shan. The precipitous mountain trail was so narrow that it was only wide enough for one person to pass at a time. According to Li Zhongquan: ‘one misstep, and you were gone – we had our sandals soled with iron to get over the mountain’. Li also remembers when: ‘one of us was sick and fell dead on the mountain top in winter. We had to leave him there until the snow thawed in spring, when we carried the body down home’. The porters carried tea from Tianquan to Kangding, and returned with loads of medicinal herbs (especially Cordyceps sinensis of Chinese caterpillar fungus), musk, wool, horn and other Tibetan products. The four porters interviewed in China Daily did not know for sure when the tea portage trade had started in Ganxipo, but Li was certain that ‘my grandpa’s grandpa was a porter as well,’ and that the whole village had offered porter services for generations."

Source:[www.cpamedia.com/trade-routes...l-perspective/] Author: Andrew Forbes, David Henley, China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2 (Source (of book quote) information received via OTRS Ticket:2012091010014712. Rjd0060 (talk) 13:02, 11 September 2012 (UTC)

Just walking for a few kilometers on a flat surface with 40 Kg worth of material on your back, I can attest is already exhausting. To imagine tripling that weight, walk for over 180 kilometers over mountain trails, and breathe rarefied air? I wouldn't say it's downright impossible, but highly improbable. I too, would agree that it was likely only exceptions rather than the rule.Forfatter/Opretter: Redgeographics, Licens: CC BY-SA 4.0

Map of the Tea-Horse road